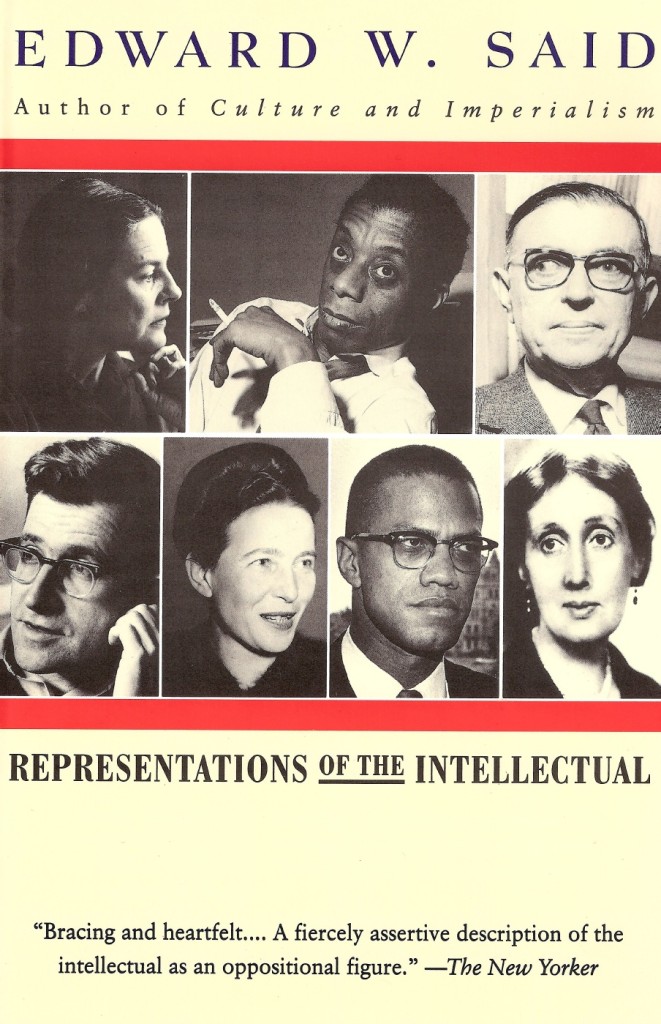

I just finished reading Representations of the Intellectual, by Edward Said. In this slim volume, a collection of six lectures weighing in at 121 pages, Said explores the role of the public intellectual in our post-industrial society.

I just finished reading Representations of the Intellectual, by Edward Said. In this slim volume, a collection of six lectures weighing in at 121 pages, Said explores the role of the public intellectual in our post-industrial society.

Said argues that it is the sacred charge of the intellectual to uphold universal principles that must be applied regardless of who is in power or what special circumstances arise. The intellectual holds friend and foe alike to the same standard – relentlessly inviting, persuading and confronting the principalities and powers to acknowledge their limits and moral responsibility. He or she reminds today’s rulers that their authority is contingent, and that they are ultimately accountable to a standard beyond the dictates of realpolitik.

For Said, a true intellectual is one who does not allow herself to become so compromised by loyalty to a cause, ideology, nation or party that she is no longer able to speak openly and truthfully to the pressing issues of the day. Said argues for a fearless class of intellectual who remains always an amateur. He laments the rise of pervasive professionalization that has rendered so many public thinkers mere employees. When considerations of personal advancement, reputation and loyalty become more important than the truth, a person is no longer an intellectual in the truest sense.

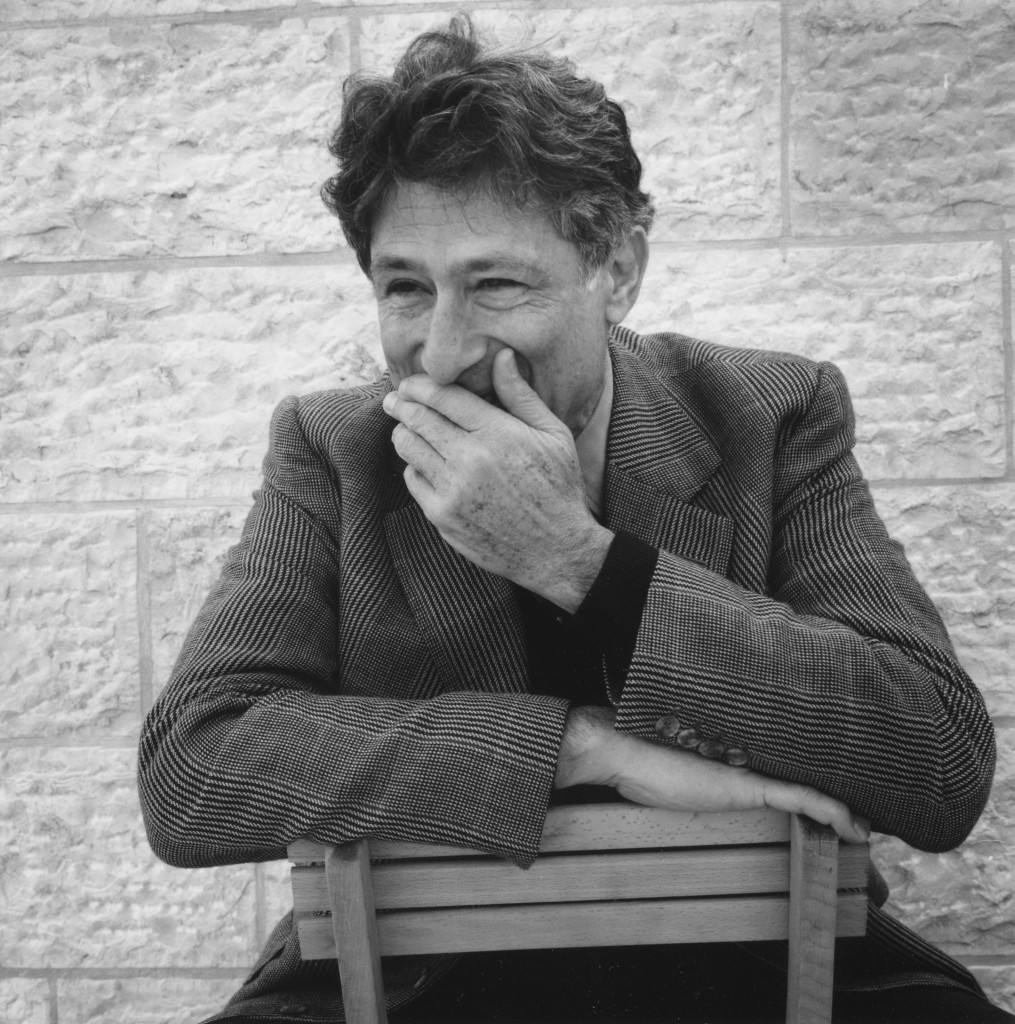

I find in these lectures a resonance that goes back much farther than the modern Arab and European intellectual traditions in which Said was so steeped. For me, Said’s vision of the fearless public intellectual reads as a riveting exploration of what it means to be a prophet in our (post)modern world. In all fairness, Said might have cringed at this take on his work. A self-described agnostic, Said comes across as gently dismissive of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Yet I am impressed with how, despite his negative view of the biblical witness, he ultimately came to express a vision of the intellectual that in many ways mirrors the rather unpleasant, thankless, and often dangerous work of the Hebrew prophets.

I find in these lectures a resonance that goes back much farther than the modern Arab and European intellectual traditions in which Said was so steeped. For me, Said’s vision of the fearless public intellectual reads as a riveting exploration of what it means to be a prophet in our (post)modern world. In all fairness, Said might have cringed at this take on his work. A self-described agnostic, Said comes across as gently dismissive of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Yet I am impressed with how, despite his negative view of the biblical witness, he ultimately came to express a vision of the intellectual that in many ways mirrors the rather unpleasant, thankless, and often dangerous work of the Hebrew prophets.

Certainly, there are important differences – most fundamentally in the realm of authority. Said chooses to make abstract, philosophical values (for example, that racism is wrong) the touchstone for his ideal intellectual. For the Old Testament prophets and those who have followed in their footsteps, the point of reference must always be the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Functionally, however, Said’s intellectual serves the same purpose as the biblical prophet. Using whatever symbolic means at his or her disposal – words, music, poetry or public performance – the intellectual/prophet exposes the heart of the matter, the way things really are, whether those in power like it or not.

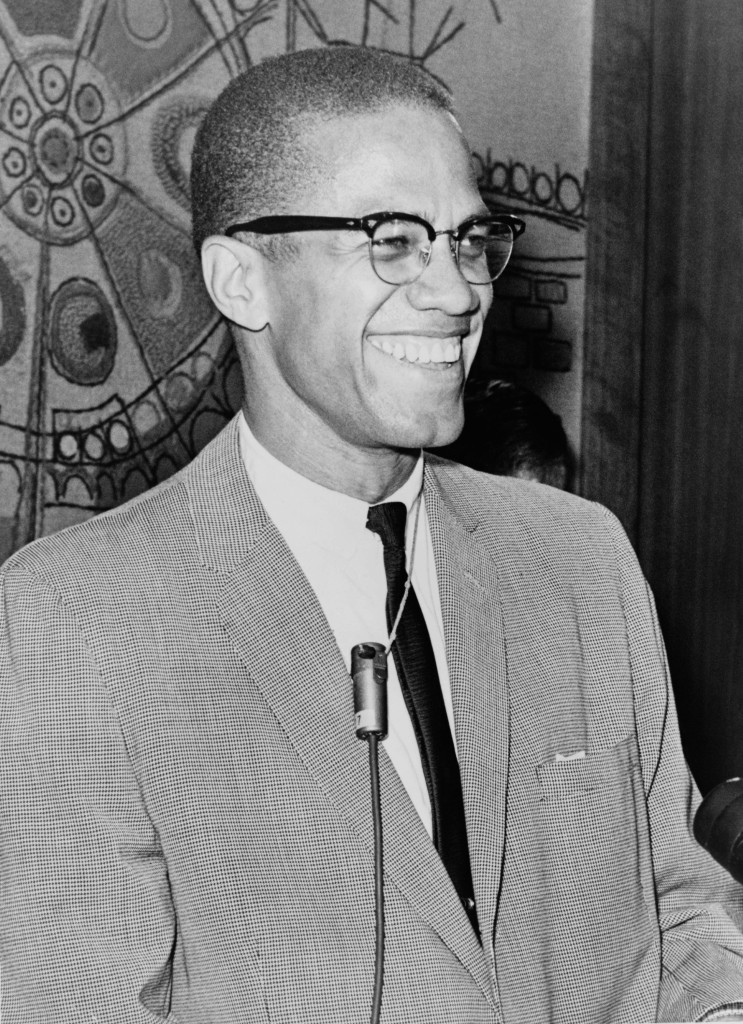

We know from the stories of the biblical prophets, as well as from the many prophets/intellectuals who have shaped our world in the last two thousand years, that there is often a high price to pay for carrying out this work of truth-telling. To publicly display truth can have serious consequences when those in power depend on the cover of darkness to maintain their grip on society. The true prophets/intellectuals are often beaten, killed, exiled – anything to shut them up and keep the deceitful dance going.

We know from the stories of the biblical prophets, as well as from the many prophets/intellectuals who have shaped our world in the last two thousand years, that there is often a high price to pay for carrying out this work of truth-telling. To publicly display truth can have serious consequences when those in power depend on the cover of darkness to maintain their grip on society. The true prophets/intellectuals are often beaten, killed, exiled – anything to shut them up and keep the deceitful dance going.

Despite the violent reaction that they inspire, however, the prophet/intellectual is truly a friend to the whole of society – even, ultimately, the elites that silence them. Neither Said’s intellectual nor the biblical prophet is against the rulers. In fact, a society that heeds the words of the prophet/intellectual will be healthier, more just, and generally avoid catastrophe. That’s good news for everybody, whether presidents or fast food workers.

Unfortunately, we generally choose to follow gods of our own making rather than acknowledging the inconvenient truth. Said spends a lot of time in these essays talking about humanity’s false gods. Whether political ideologies, tribal loyalties or the simple lure of wealth and acclaim, there are so many things that have the appearance of ultimacy, but which are not, in fact, ultimate. We worship them at our own peril.

Just like the biblical prophet, Said’s intellectual exists to call us out of our idolatry and back into an honest, soul-searching encounter with life as it really is. This divine encounter rejects the false certainty of fundamentalism, whether religious or secular. Instead, the prophet/intellectual invites us to embrace a risky faith that remains open to doubt, dialogue and change.

Just like the biblical prophet, Said’s intellectual exists to call us out of our idolatry and back into an honest, soul-searching encounter with life as it really is. This divine encounter rejects the false certainty of fundamentalism, whether religious or secular. Instead, the prophet/intellectual invites us to embrace a risky faith that remains open to doubt, dialogue and change.

Said writes that the true intellectual is a secular being – secular in the sense that the his words and actions are firmly grounded in the concrete realities of life as it is really lived. Static, propositional ideology – whether the Nicene Creed or the Communist Manifesto – can never be the starting place for real faith. Christ is revealed when we encounter him in the midst of our everyday lives – in our work for greater health, prosperity, reconciliation and justice in our neighborhoods and on the international stage.

In her work, the prophet/intellectual has no room for canned dogma that takes precedence over the real, urgent concerns of living individuals and communities. Of what value are platitudes about freedom and democracy when our foreign policy destroys lives, families, nations? What do we gain by parroting cheap stock phrases about Jesus while denying the resurrection through our hardness of heart, our unwillingness to open our lives and share with others?

As prophets, as intellectuals in the sense that I believe Said meant to use the word, the first step is to see the truth about ourselves. Are we ready to recognize the false gods that we are serving? Will we face the ways in which we compromise the gospel in order to get along, avoid conflict and ensure our own comfort? Only acknowledging the truth about our own lives will prepare us to serve as clear-eyed truth tellers in our communities, our nations and beyond.